- Home

- Lauren Tarshis

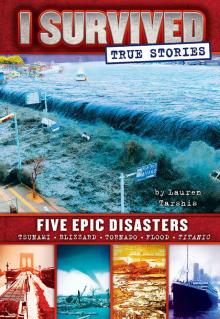

I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters

I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters Read online

by Lauren

Tarshis

FIve epIC dISaSTerS

TSUNAMI

• TITANIC

• BLIZZARD

• TORNADO

preSS

• FLOOD

Five ePiC Disasters

THE SINKING OF THE

TITANIC

, 1912

THE SHARK ATTACKS OF 1916

HURRICANE KATRINA, 2005

THE BOMBING OF PEARL HARBOR, 1941

THE SAN FRANCISCO EARTHQUAKE, 1906

THE ATTACKS OF SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG, 1863

THE JAPANESE TSUNAMI, 2011

THE NAZI INVASION, 1944

THE DESTRUCTION OF POMPEII, AD 79

ALSO BY LAUREN TARSHIS

Five ePiC Disasters

by Lauren Tarshis

ScholaStic PreSS / New York

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled,

reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and

retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now

known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions

Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012.

e-ISBN 978-0-545-78974-5

Text copyright © 2014 by Lauren Tarshis

All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Press, an imprint of Scholastic Inc.,

Publishers since 1920. scholastic,scholastic press, and associated logos are

trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available.

First printing, October 2014

Designed by Deborah Dinger, Yaffa Jaskoll, and Jeannine Riske

To all of you amazing readers, who

make writing such a joy.

Contents

viii AUTHOR’S NOTE

1

1: THE CHILDREN’S BLIZZARD,

1888

31

2: THE

TITANIC

DISASTER, 1912

63

3: THE GREAT BOSTON MOLASSES

FLOOD, 1919

91

4: THE JAPANESE TSUNAMI, 2011

119

5: THE HENRYVILLE TORNADO, 2012

145 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

146 MY SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

151 PHOTO CREDITS

166 ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Dear Readers,

Over the past few years, I’ve received thousands

of notes and e-mails from you, asking amazing

questions — about writing, about research, about

my family, and of course about my dog. But one

of the most common questions has been: What

was the inspiration for the I Survived series?

The answer is in this book.

When I’m not writing the I Survived books, I’m

doing my job as editor of the Scholastic magazine

Storyworks, which is read by more than 700,000

kids in their classrooms. The heart of every issue

of Storyworks is a thrilling nonfiction article, and

over the years I have written dozens and dozens

of these articles myself. There are fascinating true

stories about a huge range of subjects — incredible

journeys and heroic people, death-defying rescues

and real-life monsters, amazing inventions and

shocking discoveries.

And, of course, I’ve written about disasters —

tornadoes and shipwrecks and hurricanes and

volcanoes and earthquakes and even a flood of

molasses that filled the streets of Boston. I’ve

written so many disaster stories for Storyworks

that one friend nicknamed me “the disaster

queen.” I decided that was a compliment!

It was while writing these stories that I had the

idea for the I Survived series. But it’s not really

the disasters themselves that captivate me. Sure,

it’s interesting to read about spewing lava and

wild waves and winds whirling at 200 miles per

hour. But what really fascinates me are the people

in these stories — ordinary people who behave in

heroic ways, who endure terrible events and go

on to live happy lives. It’s this human quality —

resilience — that inspires me, and is at the heart

of each of the I Survived books.

The stories you’re about to read have appeared

in Storyworks in recent years, though I’ve expanded

them for this collection and added new facts and

interesting tidbits. Though the I Survived books

are historical fiction, I think you’ll see many simi-

larities between those books and the nonfiction

articles that follow.

Thank you all for making me a part of your

reading journey!

#1

THE CHILDREN’S

BLIZZARD, 1888

January 12, 1888, dawned bright and sunny in

Groton, Dakota Territory, a tiny town on America’s

enormous wind-swept prairie. For the first time

in weeks, eight-year-old Walter Allen didn’t feel

like he was going to freeze to death just by waking

up. He kicked off his quilt and hopped out of

bed with hardly a shiver. Within minutes he had

thrown on his clothes, wolfed down his porridge,

and kissed his mom good-bye. With a happy

wave, he hurried off to school, a four-room

schoolhouse about a half mile from his home.

All across Dakota Territory and Nebraska that

morning, thousands of children like Walter headed

to school with quicker steps than usual. For weeks

they’d been trapped in their homes by

dangerously cold weather. In some areas, the

temperature had plunged to 40 degrees below zero.

It was cold enough to freeze a person’s eyes shut and

turn their fingers blue and their toes to ice. Schools

all through the region had been closed. Parents kept

their kids inside, huddled close to stoves.

At least Walter’s family lived in a proper house,

on Main Street. His dad, W. C., was a lawyer and

a successful businessman. But most of the people

living on this northern stretch of prairie were

brand-new settlers. They had come from Europe,

mainly Sweden, Norway, and Germany. The

majority were very poor and struggling to survive

in this punishing land. Without money to buy a

house or building supplies, thousands lived in

bleak sod houses, tiny dwellings built from bricks

of hardened soil. Life in a cramped, smoky “soddy”

was never easy. Being trapped inside for weeks was

torture.

What a relief it was to be back at school! It was

still cold outside, only about 20 degrees. But after

the weeks of frozen weather, the

air felt almost

springlike. Many kids left home without their

warm wool coats and sturdy boots. Walter wore

just his trousers and woolen shirt. Girls wore their

cotton dresses and leather shoes, their braids

swinging merrily from their hatless heads. As

children arrived at Walter’s school, some stood

outside on the steps. They admired the unusual

color of the sky — golden, with just a thin veil of

clouds. “Like a fairy tale,” one of them said.

AN ARCTIC BLAST

But not everyone was smiling at the surprisingly

warm weather and the glowing sky. Some people

had learned the hard way that they should never

trust the weather on America’s northern prairie,

especially in the winter. Wasn’t there something

spooky about the color of the sky? Wasn’t it odd

that the temperature had jumped more than forty

degrees overnight? A Dakota farmer named John

Buchmillar thought so. He told his twelve-year-

old daughter, Josephine, that she’d be staying put

that day. “There’s something in the air,” he said to

her with a worried glance at the sky.

There was indeed something in the air, and

it was headed directly toward America’s vast

midsection. High up in the sky, three separate

weather systems — masses of air of different

temperatures — were about to crash together.

The warm air that had delighted the school-

children that morning would soon smash into a

sheet of freezing Arctic air speeding down from

Canada. Most dangerous of all was a low-pressure

system — a spinning mess of unstable air churning

its way across the continent from the northeast.

The meeting of these three weather systems would

soon create a monstrous blizzard, a frozen white

hurricane of terrifying violence.

But Walter Allen and his classmates had no

idea what was brewing above them in the endless

prairie sky. Not even the experts knew what was

coming. First Lieutenant Thomas Woodruff,

trained in the brand-new science of weather

forecasting, was working at his office in Saint

Paul, Minnesota. It was Woodruff’s job to gather

In a true blizzard, so much snow fills the air

that it can be impossible to see.

information about the weather, including the

temperature and wind speeds, in surrounding

areas. Using this information, Woodruff would

try to predict what weather was heading down to

the area around Groton.

At 3:00 p.m. the day before, Woodruff had

sent out his prediction for the following day.

His forecast would be printed in small-town

newspapers.

“For Minnesota and Dakota: Slightly warmer

fair weather, light to fresh variable winds.”

AN EXPLOSION

All morning Walter Allen sat at his desk working

on his arithmetic problems. His teacher walked

through the room offering help, her skirt swishing

and her boots clicking against the wooden floor.

The children worked on their small rectangular

chalkboards, which were called writing slates.

After finishing each set of problems, Walter took

a tiny glass perfume bottle from his desk, removed

the jewel-like lid, and

poured a drop of water

onto the hard surface of

his slate. The bottle was

Walter’s prized possession.

All of the other children kept small

bottles of water and rags at their desks to wipe

their slates clean. But Walter’s bottle was special,

a treasure that seemed to be plucked from a

pirate’s chest.

He was just finishing his problems when a

roaring sound overtook the school. The walls

began to shake, the door rattled, and some of the

younger children began to cry. Walter rushed to

the window and was stunned by what he saw.

“It was like day had turned to night,” one

farmer later wrote in his journal. From out of

nowhere, sheets of snow and ice pounded the

school.

Fortunately the men of the small, tight-knit

town of Groton mobilized quickly when the

storm hit. As the teachers gathered the children

in front of the school, they were relieved to

discover that five enormous horse-drawn sleds

were already there, ready to take everyone home.

The teachers kept careful track of every child

who climbed onto a sled, checking off names in

their attendance books. When every child was

accounted for, the sleds began to move.

SWALLOWED BY DARKNESS

Walter’s sled was creeping slowly away from the

school when he remembered his perfume bottle.

He knew the delicate glass would never survive in

such cold temperatures: The water inside would

freeze, and the bottle would shatter.

Nobody saw Walter Allen as he jumped down

from the sled and hurried back into the school. It

took him just a few seconds to grab his bottle,

stuff it into his pocket, and rush back outside.

But the sleds had vanished — swallowed by

the sudden darkness. Walter tried to run into the

street, but the wind spun him and knocked him

over. He stood up, took two steps, and the wind

swatted him down again. Up and down, up

and down.

Meanwhile, snow and ice swarmed around

Walter’s body like attacking bees. Snow blew up

his nose, into his eyes, and down the collar of his

shirt. His face became encrusted in ice, and

his eyes were soon sealed shut by his frozen tears.

He managed to stand one final time, desperate

now. But he was no match for this monstrous

storm. Once more the wind slammed Walter

down. This time he could not stand up, so he

curled himself into a ball, too exhausted to move.

He realized that nobody knew that he wasn’t

on the sleds, huddled among classmates, heading

for home. It was as though he had tumbled

off Earth and into space — a frozen, swirling

darkness.

THE LONG WINTER

Brutal winters were always a part of life on

America’s northern plains. Native American

tribes first settled the area 1,500 years ago, hunting

buffalo across the flat, grassy plains. But most

tribes migrated south for the winters, returning

after the worst of the snows had passed.

Few of the white settlers who came to the plains

were prepared for the hardships and loneliness of

life on the prairie. Many were driven away — or

A young steer

after a blizzard

killed —by the deadly winters. “There was

nothing in the world but cold and dark and

work . .. and winds blowing,” remembers Laura

Ingalls Wilder in her book The Long Winter. The

book, part of the famous Little House series,

describes the Ingalls family’s terrifying experiences

in the Dakota Territory during

the snowy winter

of 1880–81. At one point, trains carrying food and

coal were stranded due to snowdrifts. The family

and others in the town nearly starved.

But the storm of 1888 was different from

even the most brutal prairie blizzards. It hit so

suddenly — a gigantic wave of wind, ice, and snow

that crashed over the prairie without warning. As

Walter Allen lay freezing on the ground in Groton,

thousands of other children across the Great Plains

were also caught in the storm.

Some teachers had kept their children at school,

gathering them together in front of wood-burning

stoves, calming the young ones with stories and

songs. Minnie Freeman, a seventeen-year-old

teacher in Mira Valley, Nebraska, hoped to keep

her sixteen students safe in their tiny

schoolhouse. But within an hour, the winds had

ripped a hole in the roof, and Minnie knew they

would all freeze unless they found shelter. She

tied the children together with a rope and led

them through the storm, sometimes crawling

along the ground to escape the winds. Somehow

they made it to the boardinghouse where Minnie

lived — cold but alive.

RESCUE MISSION

There were other lucky children that day, saved

by quick-thinking teachers or, more often, small

miracles. There were the Graber boys, who were

lost on the prairie until they glimpsed a familiar

tree, enabling them to find their bearings and get

to their home. There was eleven-year-old Stephan

Ulrich, who was lost, freezing, and nearly blind

when he crashed into the side of a barn. Feeling

his way to the entrance, he went inside and spent

the night curled up next to a hog, whose warmth

protected him from the cold.

When Walter Allen’s father, W. C., discovered

that his youngest son hadn’t come home, he and

four other men headed back to the school, risking

their lives. At the last moment, they allowed

I Survived the Battle of D-Day, 1944 (I Survived #18)

I Survived the Battle of D-Day, 1944 (I Survived #18) I Survived the Great Molasses Flood, 1919

I Survived the Great Molasses Flood, 1919 I Survived the Galveston Hurricane, 1900

I Survived the Galveston Hurricane, 1900 I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906

I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906 I Survived #4: I Survived the Bombing of Pearl Harbor, 1941

I Survived #4: I Survived the Bombing of Pearl Harbor, 1941 I Survived the Destruction of Pompeii, AD 79

I Survived the Destruction of Pompeii, AD 79 I Survived #1: I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912

I Survived #1: I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912 I Survived #5: I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906

I Survived #5: I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906 I Survived Hurricane Katrina, 2005

I Survived Hurricane Katrina, 2005 I Survived the Attacks of September 11th, 2001

I Survived the Attacks of September 11th, 2001 I Survived the Attack of the Grizzlies, 1967

I Survived the Attack of the Grizzlies, 1967 I Survived the Great Chicago Fire, 1871

I Survived the Great Chicago Fire, 1871 I Survived the Shark Attacks of 1916

I Survived the Shark Attacks of 1916 I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912

I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912 Emma-Jean Lazarus Fell Out of a Tree

Emma-Jean Lazarus Fell Out of a Tree I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters

I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters I Survived the Hindenburg Disaster, 1937

I Survived the Hindenburg Disaster, 1937 I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888

I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888 I Survived the Joplin Tornado, 2011

I Survived the Joplin Tornado, 2011 I Survived the American Revolution, 1776

I Survived the American Revolution, 1776 Emma Jean Lazarus Fell in Love

Emma Jean Lazarus Fell in Love I Survived the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863

I Survived the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863 I Survived the Japanese Tsunami, 2011

I Survived the Japanese Tsunami, 2011