- Home

- Lauren Tarshis

I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888 Page 4

I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888 Read online

Page 4

No wonder John didn’t see her.

“Help John up and let’s get him closer to the stove,” Miss Ruell said.

Peter, Rex, and Sven all lifted John to his feet and practically carried him across the room. Myra brought over a chair so he could sit. The guys hovered around him. Franny glued herself to John’s side.

But Miss Ruell shooed everyone away.

“Let him get warm,” she said.

Myra took Franny by the hand, and the guys moved away.

Miss Ruell was still covered with snow. She was untying a rope that was knotted around her waist. John realized she must have tied the other end to something in the schoolhouse. That’s how she had made sure she would be able to find her way back inside.

How smart of Miss Ruell. And brave.

She must think he was a fool, to run outside in the blizzard. She must hate him more than ever.

John took a breath.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” he said.

His teacher looked at him with surprise.

She wasn’t wearing her glasses. Her bun had come loose. Brown curls hung around her face.

She didn’t look scary.

“You thought your sister was out there,” she said. “What you did was brave.”

Their eyes locked together for a moment. A gentle smile flickered across his teacher’s face. She patted John’s arm before she walked back to her desk.

Maybe it was the fire in the stove. But suddenly, John felt warmer.

The wind screamed louder. The schoolhouse walls shuddered, and the windows rattled. But Miss Ruell, her hair back in its bun, was steely and calm.

She gave all the older kids jobs. When John was warmed up again, he helped the guys sweep away the snow that was sifting under the door and through the cracks in the walls. Myra and Annie kept watch over the little kids and soon had them playing Simon Says. Moving around helped them stay warm.

John kept his eye on Franny. But now he couldn’t stop thinking about Ma and Pa. What if Pa had been out in the field when the blizzard hit? What if Ma had been in the barn?

It was very cold in the schoolhouse, even with Miss Ruell feeding extra coal into the roaring fire in the stove. John kept looking at the coal bin. There was barely enough coal to last a few hours more. What would happen when all the coal was gone?

They’d have to burn the books, and then the desks.

And after that?

John tried not to think about it.

Suddenly, the schoolhouse door flew open with a loud bang. An icy blast of freezing air and snow exploded into the room.

The wind had ripped off the door!

But no. It wasn’t the wind.

Three men stumbled into the schoolhouse. One of them wrestled the door closed again. The men stood there, breathing hard. They were so caked with snow and ice they looked like walking snowmen.

Myra went running over.

“Papa!” she said, ignoring the snow that covered him and throwing her arms around him.

The other men were Mr. Johnson and Mr. Lowry, who owned stores in town.

“We’ve got three sleds outside,” Myra’s father said, his voice rising over the wind. “Plenty of room for everyone. Blankets, too. We’re going to get you into town, to the hotel. We can wait out the blizzard there and then get everyone home when the storm is over.”

Cheers rang out.

They’d been rescued!

Peter held up his broom and hooted.

Miss Ruell closed her eyes, looked up, and whispered something to herself. And then she clapped her hands and called the class to order.

“Everyone get their coats and wraps and line up.”

“Let’s be quick,” said Myra’s father. “Storm’s getting worse. The horses are freezing.”

Miss Ruell divided the children into three groups. She would ride in the biggest sled in the front, with the six youngest children.

Myra and Annie would take charge of three younger girls and go with Mr. Johnson in the second sled.

John and the guys would be in the third sled with Mr. Lowry.

John didn’t want to be away from Franny. But there was no way he could argue. And he knew Miss Ruell would keep her safe.

Myra’s father flung open the door, and they faced the brutal cold. It was more freezing now than it had been when John was stuck outside. The snow poured down harder. It was like standing under a waterfall made of snow and ice. Within seconds they were all covered.

John held Franny’s hand tight as they pushed through the wild, frozen swirl. There were lanterns on each sled. The lanterns cast a ghostly yellow light, just enough to show the outline of the sleds. Each was a simple wooden wagon mounted on metal sled rails, and hitched to a single horse. John felt so sorry for those horses. Their fur wasn’t much protection in cold this harsh. He wondered how long they’d be able to stand it.

John lifted Franny into the first wagon and made sure she was wrapped in a blanket.

It was useless to try to talk over the screaming, hissing wind. He hugged his sister tight and then hurried back to his sled. He climbed up and settled down next to Rex. Mr. Lowry was already in the driver’s seat, holding the reins.

John and the guys had one big blanket to share. They put it over their heads, to try to keep the snow and ice out of their faces. But it was useless. The snow was ground up so fine it completely filled the air. The glassy ice raked at his eyeballs, like tiny claws. John sat there, miserable and shivering. But he reminded himself that they were close to town — the trip shouldn’t take more than ten minutes. The guys weren’t complaining, were they? John had to be tough.

Finally, the first sled started to move, and its yellow glowing lantern light disappeared. The second sled followed. Mr. Lowry was about to snap the reins to get their horse moving. But just then the wind let out a vicious howl. There was a crunch, and a hunk of the schoolhouse roof came flying through the air. It smacked the horse on the back.

The horse reared in terror. The sled rocked and almost tipped over. Mr. Lowry tumbled out onto the ground. The horse took off in panic, dragging the sled — and John and the guys — along with it.

And now they were speeding through the blizzard, out of control.

Rex crawled forward and tried to grab hold of the reins. But it was hopeless. The horse was running so fast the sled was practically off the ground. It rocked back and forth like a tiny boat on a storm-tossed ocean. Every time the sled hit a bump, the wood cracked and groaned.

“We have to jump!” Rex screamed.

He was right. Any moment the sled was going to break apart. They could be trampled under the horse’s hooves or crushed by the sled.

“Go!” Rex cried.

Heart hammering, John struggled to his feet. He closed his eyes, held his breath, and threw himself off the side.

He landed hard, and rolled away as the metal sled rail sliced by him, inches from his head. John lay there, panting.

Finally, he sat up. To his relief, Sven was right next to him. And Rex and Peter were behind. They all crawled closer to each other and sat in a huddle.

Nobody had gotten hurt from the jump off the sled. But they were all shivering — hard. John’s hands and feet were completely numb. They couldn’t last out here for much longer.

Rex was looking all around.

“We’re near the Ricker farm,” he shouted.

The Rickers had a real wooden house, with three rooms.

“I’m pretty sure the house is right over there,” Rex shouted.

“Where?” Sven shouted back.

Rex looked around.

“Close!”

John’s heart sank.

Close.

That word meant nothing in a blizzard like this. The schoolhouse had been just a few feet away while John was staggering around the schoolyard. If Miss Ruell hadn’t come to rescue him, he’d be a frozen corpse by now, buried in the snow.

It would be almost impossible to find the Ricker house. It

might as well be on the moon.

But they had two choices: Get moving or freeze to death right here. So when Rex shouted, “Come on!” they all struggled to their feet and followed.

They staggered through the wall of slashing snow and ice. The wind’s nonstop scream burrowed through John’s skull, deep into his brain. It was taunting John, hissing at him as he tried to push his way forward.

You’re weak.

You can’t make it.

You’re doomed!

That wind was right. John didn’t belong out here in Dakota. He’d always known it. And now he’d never escape.

John walked with his head down, crouched over like an old man, pushing himself through the wall of wind and ice and snow. He could make it only a few steps without falling. One of his friends would grab his arms and yank him back up. And then Rex would fall down, or Peter or Sven. And it would be John helping lift them up.

On and on they went. Battered by the maniac wind. Lashed by the ground-glass ice. Falling down. Standing up. Falling down. Standing up.

Colder, colder, colder.

And then came a savage gust. An ice-packed whirl so furious it knocked them all down at once.

And this time, not one of them could stand back up. Not even Rex.

They sat there, sinking deeper into the snow.

John felt the last of his body’s warmth seeping out of him, like blood leaking from a deep cut.

That screaming wind was right, John thought.

They were doomed.

Precious minutes ticked by, and none of them moved. It was getting colder.

But down here, close to the ground, the wind wasn’t quite as strong. The air wasn’t as thick with swirling snow. John managed to wipe the frozen snow from his eyes.

Which is why he saw it, the outline of something very big, just a few yards ahead.

“There’s the house!” John shouted.

They all lunged forward, crawling desperately through the snowdrifts.

John’s heart pounded with excitement.

They’d made it! They’d be safe!

The boys pushed themselves along, fighting their way forward. It wasn’t until they were just inches away that they saw that it wasn’t the Ricker house.

It was a big haystack.

Peter let out a big sob.

Rex cursed and looked around.

“The house must be this way!” he shouted.

Rex stepped forward, but John grabbed the back of his jacket and pulled him back.

“No!” John shouted.

John might not be a real pioneer like Rex. This was only his second Dakota winter. But he knew this for sure: They’d never find the Ricker house, not in time. They had to get out of this wind and snow. They had to try to get warm.

Inside the haystack.

John remembered the fox that had hidden in their haystack overnight. Didn’t Rex say that animals were always right?

John turned to Rex. “We won’t make it,” he shouted over the wind. “We have to take cover in here.”

And now John took the lead.

He punched a hole through the thick crust of snow and ice that covered the haystack. He reached through and grabbed fistfuls of the soft hay to make space. Rex and Peter and Sven were helping him. They worked desperately, jabbing their hands in, pulling out hay.

They all worked together until they had a little cave, big enough for them all to fit. And then they crawled in, lying flat and squeezed together.

It was still freezing cold. John’s numb hands and feet felt like blocks of wood. He couldn’t stop shivering. But finally the cruel wind couldn’t reach them. The ice and snow couldn’t tear at their faces. And soon the heat from their bodies started to warm up the small space.

“Don’t sleep,” Rex said.

John had heard what happened to people who fell asleep in the freezing cold.

They never woke up. That’s why freezing to death wasn’t the worst way to die, he’d heard. Because you fall asleep before your heart stops.

And so now they fought hard against sleep, just like they’d fought against the wind and snow. They took turns telling stories. They counted to one thousand and then did it again backward. They said prayers. John told them the name of every player on the Chicago White Stockings.

The hours passed. The blizzard raged on. They ran out of stories and got tired of counting. And then Peter started muttering in a strange, rhyming way. And John realized he was reciting one of the long, boring poems Miss Ruell had made them memorize. They all joined him. And then they recited another, and another. They all knew so many.

It turned out that not all of those poems were so boring. Some were about pirates and sailors. One was about the summer, and the words made John feel warmer. There were poems that made no sense, like one about a pig wearing a wig. But it actually made them laugh.

Those poems kept them up for hours more.

But finally, their voices became ragged.

Their words faded away.

John’s mind started to drift.

Don’t sleep! Don’t sleep!

His eyes fluttered.

Don’t sleep! Don’t sleep!

John’s eyes shut.

Don’t sleep, don’t …

John’s eyes stayed closed.

Everything got quiet, even the sound of that screaming wind.

Was this ferocious storm finally dying?

Or was John?

Newspapers from New York to Seattle printed stories about the deadly blizzard that had struck America’s northern prairie.

It was one of the most powerful snowstorms ever to hit America, more like a frozen hurricane than a blizzard. Winds had reached 70 miles an hour. Temperatures had dipped down to minus 40. Cities like St. Paul, Minnesota, and Lincoln, Nebraska, were shut down. Towns were buried. Hundreds were dead.

It was a blizzard so terrible that soon it had a name:

The Children’s Blizzard.

Because at least one hundred of the people who died were schoolchildren.

The newspapers were filled with sad and terrible stories about children who became trapped in the frozen, swirling winds.

But there were miracles, too.

Like how one teacher tied her ten students together with a rope and led them to a farmhouse a half mile away from their school. Or the kids who made it through the night in a shelter they built from snow. Or the brothers who huddled in a barn with two pigs that kept them warm.

And the four boys from the tiny town of Prairie Creek, Dakota, who survived the blizzard in a haystack.

John didn’t read any of those stories, not at first.

For the first week after the blizzard, he wasn’t sure if he was alive or dead. The storm had ended just a few minutes after he and the guys had fallen asleep. They had been in that haystack almost all night.

John was barely breathing when Mr. and Mrs. Ricker carried him and the other boys from the haystack and into the farmhouse. When Ma and Pa got there, later that day, he heard them calling his name. He felt their hands on him.

But he couldn’t open his eyes. He couldn’t move or speak. He felt locked away, caught in a frozen nightmare.

Most of the time, he thought he was still in the haystack, or curled into a snowdrift. That hissing blizzard scream still echoed in his ears.

It wasn’t until a week after the blizzard that John finally opened his eyes. It was the middle of the night, and it took him a long, panicked moment to understand that he wasn’t in the haystack. Or in a frozen grave.

He was in the warm soddy, tucked into his bed. Franny was curled up next to him. Pa was dozing in a chair, pulled close. Ma was sitting on John’s bed.

“Ma?” John said, in a crackling voice.

The fire in the stove cast a golden glow, and John saw the tears in Ma’s eyes as she smiled down at him.

And that was the moment when, for John, the terrifying blizzard at last came to an end.

The snow had melted, a

nd the prairie was slowly sprouting back to life. Bright green shoots pushed up through the brown grass. Enormous flocks of geese and ducks flapped across the blue sky.

The winter was over. The birds were back.

John and the guys had returned to school at the end of March. And now, on this bright and warm day in April, here they were at the creek.

They’d come for King Rattler.

John had brought Pa’s rifle this time. Rex clutched his ax, and Sven was ready with his stick. Peter had found a dead rabbit, half-eaten by a fox. That was the bait.

“King Rattler could attack from any direction,” Rex reminded them, his voice strong but still raspy from months of coughing. He’d caught a bad case of pneumonia after the blizzard, and looked too skinny and frail.

They were all still healing.

Sven lost two toes from frostbite and was walking with a cane.

Peter had lost a pinky.

“I never liked that finger anyway,” he swore.

John’s feet had been so badly frostbitten that he nearly lost them — his hands, too. His feet had swelled up like balloons. The skin on his hands and feet turned black, like meat left too long on the fire. The pain was so terrible that he couldn’t move. For days he was in bed, soaked in sweat and trying not to cry.

But Ma kept telling him that the pain was good news, that it meant blood was starting to flow again, that his hands and feet were coming back to life. She kept dosing John with Brown’s Bitters and gently rubbing his skin with some cream that smelled like rotten apples.

Slowly the black skin peeled away. Underneath was brand-new skin — soft and pink.

“Your feet look like piglets!” Franny had shrieked happily.

John stared at his bright pink feet and realized Franny was right. He started to laugh, and Ma and Pa did, too. And after that, some of the gloom cleared from the soddy.

It helped that people from town kept coming to visit them. They brought food, precious jars of berry jam and baskets of eggs from their cellars. Myra visited and gave John a scarf she had knitted herself. Mr. Lowry came, and told them what happened to him after the horse bolted with the sled. He’d made it back into the schoolhouse and had burned the desks to stay warm through the night.

I Survived the Battle of D-Day, 1944 (I Survived #18)

I Survived the Battle of D-Day, 1944 (I Survived #18) I Survived the Great Molasses Flood, 1919

I Survived the Great Molasses Flood, 1919 I Survived the Galveston Hurricane, 1900

I Survived the Galveston Hurricane, 1900 I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906

I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906 I Survived #4: I Survived the Bombing of Pearl Harbor, 1941

I Survived #4: I Survived the Bombing of Pearl Harbor, 1941 I Survived the Destruction of Pompeii, AD 79

I Survived the Destruction of Pompeii, AD 79 I Survived #1: I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912

I Survived #1: I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912 I Survived #5: I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906

I Survived #5: I Survived the San Francisco Earthquake, 1906 I Survived Hurricane Katrina, 2005

I Survived Hurricane Katrina, 2005 I Survived the Attacks of September 11th, 2001

I Survived the Attacks of September 11th, 2001 I Survived the Attack of the Grizzlies, 1967

I Survived the Attack of the Grizzlies, 1967 I Survived the Great Chicago Fire, 1871

I Survived the Great Chicago Fire, 1871 I Survived the Shark Attacks of 1916

I Survived the Shark Attacks of 1916 I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912

I Survived the Sinking of the Titanic, 1912 Emma-Jean Lazarus Fell Out of a Tree

Emma-Jean Lazarus Fell Out of a Tree I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters

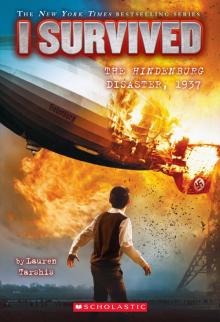

I Survived True Stories: Five Epic Disasters I Survived the Hindenburg Disaster, 1937

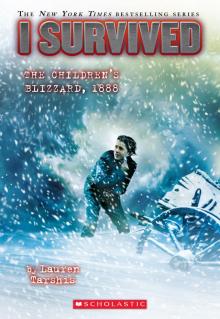

I Survived the Hindenburg Disaster, 1937 I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888

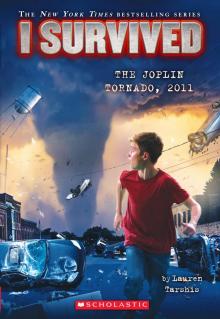

I Survived the Children's Blizzard, 1888 I Survived the Joplin Tornado, 2011

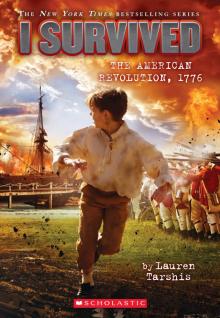

I Survived the Joplin Tornado, 2011 I Survived the American Revolution, 1776

I Survived the American Revolution, 1776 Emma Jean Lazarus Fell in Love

Emma Jean Lazarus Fell in Love I Survived the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863

I Survived the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863 I Survived the Japanese Tsunami, 2011

I Survived the Japanese Tsunami, 2011